Home » Articles posted by drannalcox (Page 6)

Author Archives: drannalcox

Talk: Games for Academic Life

Prof Anna L Cox gives keynote speech “Games for

Academic Life” at GALA 2020, Games and Learning Alliance conference.

A copy of the slides is available for download.

Media interview: Sandy Gould in The Loop

Dr Sandy Gould talks about the results of a study that we presented at the Microsoft Research New Future of Work Symposium “The New Remote Working Age” in Bridgehead Communication’s ‘The Loop’

The Global Remote Work Revolution and the Future of Work

Dave Cook, who has been collaborating with us on the eWorkLife Remote Work study has published a chapter in The Business of Pandemics book: The Global Remote Work Revolution and the Future of Work.

Media interview: Londoners urged to do ‘pretend commute’ during Covid-19 lockdown to protect health

Prof Anna L Cox is quoted in the London Evening Standard. Londoners urged to do ‘pretend commute’ during Covid-19 lockdown to protect health By Nicholas Cecil

Resisting Surveillance in Connected Cars

Dr Anna Rudnicka and Prof Anna Cox are awarded funding for a research project titled “Resisting Surveillance in Connected Cars” from the Human-Data Interaction EPSRC Network Plus

Miegunyah Distinguished Visiting Fellowship

Prof Anna L Cox has been awarded a Miegunyah Distinguished Visiting Fellowship by the University of Melbourne for 2021.

The Miegunyah Distinguished Visiting Fellowship Program enables overseas scholars of international distinction to make an extended visit to the University and contribute to the University’s academic, intellectual and cultural life. The Fellowships are awarded annually, following an application and selection process that begins with nominations from the University of Melbourne Faculties.

The fellowship will fund to visit Melbourne, Australia where Anna will give a public lecture titled “Fitter, happier, more productive? Regaining control of our mobile technologies in the digital age” and collaborate with colleagues in the School of Computing and Information Systems.

Media interview: Technology is easier than ever to use — and it’s making us miserable

Prof Anna L Cox is quoted in Technology is easier than ever to use — and it’s making us miserableby Shubham Agarwal

Honorable Mention Award @ CSCW 2020

Yoana Ahmetoglu, PhD student at UCLIC, receive an Honourable Mention Award for her paper To Plan or Not to Plan? A Mixed-Methods Diary Study Examining When, How, and Why Knowledge Work Planning is Inaccurate (co-authored with Duncan P Brumby and Anna L Cox)

Talk: Facing the Future: what lessons have we learned?

Prof Anna L Cox gives an invited talk at the Facing the Future: what lessons have we learnt? event to celebrate National Work Life Week 2020.

Remote-work visas will shape the future of work, travel and citizenship

During lockdown, travel was not only a distant dream, it was unlawful. Some even predicted that how we travel would change forever. Those in power that broke travel bans caused scandals. The empty skies and hopes that climate change could be tackled were a silver lining, of sorts. COVID-19 has certainly made travel morally divisive.

Amid these anxieties, many countries eased lockdown restrictions at the exact time the summer holiday season traditionally began. Many avoided flying, opting for staycations, and in mid-August 2020, global flights were down 47% on the previous year. Even so, hundreds of thousands still holidayed abroad, only then to be caught out by sudden quarantine measures.

In mid-August for example, 160,000 British holiday makers were still in France when quarantine measures were imposed. On August 22, Croatia, Austria, and Trinidad and Tobago were added to the UK’s quarantine list, then Switzerland, Jamaica and the Czech Republic the week after – causing continued confusion and panic.

This insistence on travelling abroad, with ensuing rushes to race home, has prompted much tut-tutting. Some have predicted travel and tourism may cause winter lockdowns. Flight shaming is already a cultural sport in Sweden, and vacation shaming has even become a thing in the US.

Amid these moral panics, Barbados has reframed the conversation about travel by launching a “Barbados Welcome Stamp” which allows visitors to stay and work remotely for up to 12 months.

Prime Minister Mia Mottley explained the new visa has been prompted by COVID-19 making short-term visits difficult due to time-consuming testing and the potential for quarantine. But this isn’t a problem if you can visit for a few months and work through quarantine with the beach on your doorstep. This trend is rapidly spreading to other countries. Bermuda, Estonia and Georgia have all launched remote work-friendly visas.

I think these moves by smaller nations may change how we work and holiday forever. It could also change how many think about citizenship.

Digital nomads

This new take on visas and border controls may seem novel, but the idea of working remotely in paradise is not new. Digital nomads – often millennials engaged in mobile-friendly jobs such as e-commerce, copywriting and design – have been working in exotic destinations for the last decade. The mainstream press started covering them in the mid-2010s.

Fascinated by this, I started researching the digital nomad lifestyle five years ago – and haven’t stopped. In 2015, digital nomads were seen as a niche but rising trend. Then COVID-19 paused the dream. Digital nomad Marcus Dace was working in Bali when COVID-19 struck. His travel insurance was invalidated, and he’s now in a flat near Bristol wondering when he can travel.

Dace’s story is common. He told me: “At least 50% of the nomads I knew returned to their home countries because of CDC and Foreign Office guidance.” Now this new burst of visa and border policy announcements has pulled digital nomads back into the headlines.

So, will the lines between digital nomads and remote workers blur? COVID-19 might still be making international travel difficult. But remote work – the other foundation of digital nomadism – is now firmly in the mainstream. So much so that remote work is considered by many to be here to stay.

Before COVID-19, office workers were geographically tethered to their offices, and it was mainly business travellers and the lucky few digital nomads who were able to take their work with them and travel while working. Since the start of the pandemic, many digital nomads had to work in a single location, and office workers have become remote workers – giving them a glimpse of the digital nomad lifestyle.

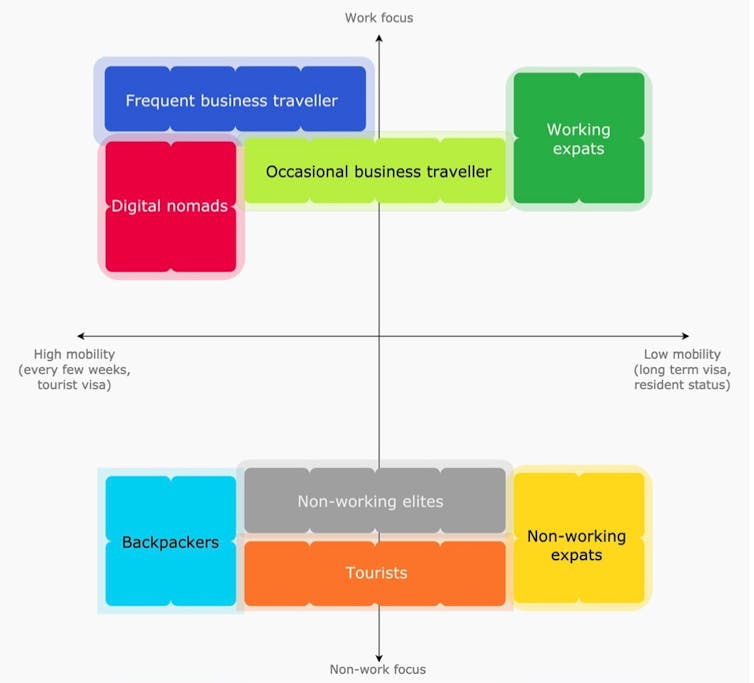

© Dave Cook and Tony Simonovsky, Author provided

COVID-19 has upended other old certainties. Before the pandemic, digital nomads would tell me that they despised being thought of as tourists. This is perhaps unsurprising: tourism was viewed as an escape from work. And other established norms have toppled: homes became offices, city centres emptied, and workers looked to escape to the country.

Given this rate of change, it’s not such a leap of faith to accept tourist locations as remote work destinations.

A Japanese businessman predicted this

The idea of tourist destinations touting themselves as workplaces is not new. Japanese technologist Tsugio Makimoto predicted the digital nomad phenomenon in 1997, decades before millennials Instagrammed themselves working remotely in Bali. He prophesied that the rise of remote working would force nation states “to compete for citizens”, and that digital nomadism would prompt “declines in materialism and nationalism”.

Before COVID-19 – with populism and nationalism on the rise – Makimoto’s prophecy seemed outlandish. Yet COVID-19 has turned over-tourism into under-tourism. And with a growing list of countries launching schemes, it seems nations are starting to “compete” for remote workers as well as tourists.

The latest development is the Croatian government discussing a digital-nomad visa – further upping the stakes. The effects of these changes are hard to predict. Will local businesses benefit more from long-term visitors than from hordes of cruise ship visitors swarming in for a day? Or will an influx of remote workers create Airbnb hotspots, pricing locals out of popular destinations?

It’s down to employers

The real question is whether employers allow workers to switch country. It sounds far-fetched, but Google staff can already work remote until summer 2021. Twitter and 17 other companies have announced employees can work remotely indefinitely.

I’ve interviewed European workers in the UK during COVID-19 and some have been allowed to work remotely from home countries to be near family. At Microsoft’s The New Future of Work conference, it was clear that most major companies were mobilising task forces and would launch new flexible working policies in autumn 2020.

Countries like Barbados will surely be watching closely to see which companies could be the first to launch employment contracts allowing workers to move countries. If this happens, the unspoken social contract between employers and employees – that workers must stay in the same country – will be broken. Instead of booking a vacation, you might be soon booking a workcation.![]()

Dave Cook, PhD Researcher, Anthropology, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.