Home » Posts tagged 'COVID19'

Tag Archives: COVID19

Adaptive, Sociable and Ready for Anything: Undergraduate Students Are Resilient When Faced with Technological Change

Elahi Hossain, Anna L. Cox, Anna Dowthwaite, and Yvonne Rogers. 2024. Adaptive, Sociable and Ready for Anything: Undergraduate Students Are Resilient When Faced with Technological Change. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 8, CSCW1, Article 198 (April 2024), 32 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3653689

The digital age has significantly altered the university experience, pushing more student interactions online and creating new dynamics in social relationships. In this paper we delve into how undergraduate students navigate and adapt to this digital shift, offering insights into their resilience and adaptability.

Key Findings:

- Adaptation to Digital Shifts: The study found that undergraduate students are remarkably adaptable to extensive digital learning environments. Despite the challenges posed by a primarily digital university experience during the COVID19 lockdowns, students utilized various digital platforms creatively to maintain and forge new social connections.

- Loss of In-Person Interactions: One major challenge highlighted was the loss of casual, spontaneous interactions available in physical settings, which are crucial for building deeper social connections. Digital environments often fail to replicate the nuanced interactions that occur naturally in person.

- Strategic Use of Digital Tools: Students demonstrated strategic use of digital tools to overcome these challenges. They chose specific platforms that supported richer, more personal interactions, such as video calls over text messaging, to better emulate face-to-face interactions.

- Building and Maintaining Relationships: The research emphasized the students’ ability to maintain pre-existing relationships and build new ones through digital means. While digital tools are not always perfect substitutes for in-person interactions, they provide vital links that help students navigate their social worlds in digital learning environments.

- Design Recommendations for Digital Learning: The paper also offers design recommendations for future ‘metaversities’ — digital campuses where interactions are more immersive. Suggestions include enhancing the richness of communication tools to better simulate in-person dynamics and designing digital spaces that promote spontaneous social interactions.

Conclusion:

This study showcases the resilience of students in adapting to a digital university environment. It highlights the importance of designing digital learning tools that support natural, rich social interactions to foster a sense of community and belonging among students, which is crucial for their social and academic success. The findings are a testament to the adaptability of the current generation of students, who are ready to navigate the challenges and opportunities presented by the digital transformation of higher education.

COVID Ward

A blogpost by Emma Holliday, student on MSc HCI 2019-2021

Getting into the video games industry was originally my inspiration for studying Computer Science. As I learned about the often toxic work environments (and sexism) in the gaming industry, I decided to leave this dream behind and went into software development instead. That’s why I’m so amazed and thrilled to have actually designed and built my own game and, even better, to have won an award for it.

Click here to play the game! Spoilers below!

The game itself was built as part of my coursework for the Serious and Persuasive Games module (led by Prof Anna Cox) on the Human-Computer Interaction course at UCL. (Even though I had somewhat given up on a career in the gaming industry, I still really loved games and would take any excuse to learn about them and play them.) Something that really stood out to me during the lectures was the concept of the “Magic Circle”, an idea that games exist within set boundaries that are separate to the real world. This means that different rules apply within game (e.g. violence is allowed), actions in the game don’t have consequences in the real world, and actions in the real world don’t apply to the game. I immediately challenged this – I’m sure we’ve all had that gaming session that left friendships a little sour even after the game had finished, learnt something new or even strengthened our relationships. I personally believe, particularly with narrative-based games, it is very unlikely to not leave some lasting impression in the real world long after the game has been played. As such, I designed a game that would exploit breaking the “Magic Circle” by including people’s real-world actions into gameplay. My hopes were that, by breaking the “Magic Circle” upfront, this would weaken the boundaries between the game and the real world, encouraging players to take experiences from the game back into real life.

My time studying this module was during the COVID-19 pandemic which also provided a lot of inspiration, largely because it was inescapable and incredibly topical. Other games which we studied during the module were also influential, particularly those on blame culture in nursing (such as Nurse’s Dilemma and Patient Panic). All of this culminated in my game, COVID Ward, where players take on the role of a nurse working in the intensive care unit during the COVID-19 pandemic. The gameplay is quite simple, players use arrow keys to control the nurse and spacebar to administer aid to patients in the ward. Patient health deteriorates over time and they will eventually die if their health becomes too low while fully healed patients are able to leave the ward. The game plays out as levels representing 12 hour shifts, so time is limited and the nurse character can only do so much in a day. In between levels is where the “Magic Circle” is broken; the player is asked a question relating to their real-world actions during the pandemic and their answer affects the number of patients admitted to the ward during the next level. For example, the question may ask if the player always wore a mask while on public transport. If the player answers “no”, there would be more patients in the ward the next day than if they had answered “yes”. Through this, players see the their actions directly associated with the effects on other people and healthcare staff.

The game was refined iteratively thanks to playtesting with my friends, fellow students, and staff on the Serious and Persuasive Games course. Finally, a user study was completed to test if the game had the desired effects of making people feel more responsible for their actions, encouraging them to follow COVID-19 safety guidance more closely and increasing empathy for nursing staff. Though it was a small scale study, initial results were very positive and suggested that the game had achieved its goal in terms of attitude change. Qualitative responses from participants repeatedly mentioned the use of their real world actions and suggested it was both engaging and encouraged them to reflect more deeply on their actions. As such, breaking the “Magic Circle” is a promising technique for persuasive games which warrants further research.

In terms of development, the game was built using Game Salad (a no-code game authoring tool). Though I’m familiar with code, (and there were times I wished I was using code!) GameSalad did provide a really quick way to get started and put ideas together without too much learning overhead. Having since tried to pick up Unity, I can say Game Salad is definitely a lot quicker to get your ideas into something working, which is crucial for iterative development. Game Salad also made it very easy to publish my game so that others could play it online, which helped enormously when getting feedback and conducting the user study as there was no installation or downloads required.

In an early version of the game, everything was represented by incredibly simple shapes and numbers. While I support the concept of primarily using the mechanic to deliver the message, as demonstrated remarkably in Brenda Romero’s games, I felt my game would benefit from graphics and sound effects to help immerse the player and reinforce the narrative that these were real people affected by their actions, encouraging stronger empathy. Given the short time frame (and that I am only one person who is not talented enough to do everything from scratch!) I was exceedingly grateful for assets created by other artists which allowed me to create something that was much more complete than I could have achieved on my own. I found the music by Bio_Unit on Free Music Archive and got sound effects from Kenney.nl (a fantastic source for several free assets!) I paid for some pixel-art assets from Malibu Darby through Humble Bundle which, very fortunately, had a game dev bundle just as I was building the game. I also dabbled in editing the pixel art myself to customise it to my game. If you’d like to give that a go, I recommend aseprite.

Overall, I was really happy with my game and the results of the user study. Prof. Anna Cox had suggested that the class submit their work to the CHI PLAY student game competition. Earlier in my time at UCL, Prof. Catherine Holloway had encouraged us to always try and share our work with the academic community and introduced me to Student Research Competitions. These are often held across different ACM conferences (such as SIGCHI, SIGACCESS, CHIPLAY) and felt much more approachable to me as the level of work expected was closer to what I had already done for my coursework. As such, I decided to go for it and submit my game and a paper detailing the user study to CHI PLAY 2021’s Student Game Design Competition. I didn’t really expect to win anything, but I was just happy to share my game in the hopes it might have a life beyond my university coursework grades.

So I was very excited when I heard back to find out my game had been accepted! It turns out, 8 of the 19 submissions were accepted to the conference as finalists. This did mean, however, that I had a bit more work to do! I updated my paper to respond to the reviewers’ comments, battled with the proper formatting and TAPS submission system (though the support staff are really helpful), and created a reaction video to be played at the conference. I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t stressful (largely because it fell right across the deadline for my final MSc dissertation!!) but it was definitely worth it to see my work presented at the conference and all the interest it generated. Even more so when I was announced as receiving an honourable mention for the competition! I also got to attend the entire conference – though you don’t have to be an author to do so – and joined lots of interesting talks and presentations across all aspects of games.

It was really rewarding finding myself back in the games industry, in a sense, but from a completely different direction than I had ever imagined and one that was much better suited to me and my passions. It was even more rewarding to know that I had contributed to it and that, maybe one day, my research will have an impact on the games I end up playing on my sofa.

Find out more about the competition and see the other entries

How the pandemic will shape the workplace trends of 2021

Elenabsl/Shutterstock

The economist John Maynard Keynes predicted in 1930 that the amount we work would gradually shrink to as little as 15 hours a week as technology made us more productive. Not only did this not happen, but we also began to spend extra time away from home due to commuting and suburban living patterns, which we often forget are recent historical inventions.

However, 2020 has changed all that. In my new history of remote work during COVID-19, I marvel at how much it has shaken up our lives and how much we took for granted. My research also points to a number of trends that will help shape working life in 2021.

Gene Daniels.

Over “in time for Christmas”

At the start of 2020 remote work was a gradually rising long-term trend. Only 12% of workers in the US worked remotely full time, 6% in the UK. Naturally the world was unprepared for mass remote work.

But COVID-19 instantly proved remote work was possible for many people. Workplace institutions and norms toppled like dominos. The office, in-person meetings and the daily commute fell first. Then the nine to five schedule, vacations and private home lives were threatened. Countries even started issuing remote work visas to encourage people to spend lockdown working in their territory.

As old norms vanished, a rapid procession of novel technologies marched uninvited into our homes. We had to master Zoom meeting etiquette, compassionate email practices, navigate surveillance, juggle caring responsibilities. The list goes on.

In the face of grim statistics – the UN predicted 195 million job losses – only the tone deaf complained about working from home. Nonetheless, COVID-19 created the biggest remote work experiment in human history.

In July, UK prime minister Boris Johnson – with Edwardian optimism – daydreamed a sense of normality would return “in time for Christmas”. Fast forward through summer to lockdown 2.0 and the fantasy of a 12-week experiment faded into sepia tinged memories. One interviewee joked: “I really thought we’d be back in the office by July, what fools we were!”

Are you disciplined?

Silicon Valley companies Google, Apple and Twitter were among the first to announce employees could work from home. Ahead of the curve, they were well practised. Predictably, they already had a fancy term for it: distributed working. In 2021 concepts such as distributed and hybrid working will proliferate.

Most were less prepared than Silicon Valley. In March, I published findings from a four-year research study tracking remote workers. I warned, to be a successful remote worker deep reserves of self-discipline were required, otherwise burnout followed.

We understand this now. But I spent the first lockdown patiently explaining to news outlets why working from home was so hard. When I suggested returning to the office might be considered a luxury – because it helped people structure their days – a news presenter laughed. For good or ill, conversations about disciplined routines will intensify in 2021.

Read more:

Remote working: the new normal for many, but it comes with hidden risks – new research

By May 2020 many reported experiencing Zoom fatigue. I naively predicted Zoom use would subside.

I’d have been right if we’d returned to the office. Instead necessity dictated we up our Zoom game – even if they were draining. Zoom simultaneously saved and ruined working from home, and it’s not going away anytime soon.

Michael D Edwards/Shutterstock

The commuting paradox

Remote workers, grateful to still have jobs, also reported a gnawing sense of survivors’ guilt. Overwork was one way of expressing this guilt. Many felt working extra hours might secure their job.

In April 2020, I joined other academics researching work-life balance on a project called eWorkLife. The research data revealed increases in working hours when it wasn’t obvious when the working day ended. Especially with no obvious signal to end the working day.

In my four-year remote study, I had noticed a strange pattern. Participants initially said “escaping the commute” was a key benefit of remote working. Yet months later these same workers started recreating mini commutes.

The eWorkLife project uncovered similar findings. People wanted to create “a clear division between work and home”. Study lead Prof Anna Cox urged people to do pretend commutes so they could maintain a work-life balance. In 2021 work-life balance must become recognised as a public health issue and the eWorkLife project is urging policymakers to act.

Khakimullin Aleksandr/Shutterstock

The right to disconnect

What’s happened to the time previously lost to commuting? Many are using it to catch up on admin and email. This taps into a worrying trend.

Pre-pandemic warnings about an encroaching 24/7 work culture were intensifying. Social scientists argued that contemporary workers were being turned into worker-smartphone hybrids. In 2016, French workers were even given the legal right to disconnect from work emails outside working hours.

A hopeful wish-list for 2021 includes continued increases in workplace activism and for companies and governments to reveal their remote working policies. Twitter and 17 other companies have already announced employees can work remotely indefinitely. At least 60% of US companies still haven’t shared their remote working policies with their employees. Remote workers tell me until bosses reveal their post-pandemic policies – planning for their future is impossible.

Read more:

Remote-work visas will shape the future of work, travel and citizenship

The late activist David Graeber described the failure to achieve Keynes’s 15-hour work week as a missed opportunity, “a scar across our collective soul”. COVID-19 may have started conversations about alternative futures where work and leisure are better balanced.

But it won’t come easily. And we will have to fight for it.![]()

Dave Cook, PhD Candidate in Anthropology, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Media interview: Sandy Gould in The Loop

Dr Sandy Gould talks about the results of a study that we presented at the Microsoft Research New Future of Work Symposium “The New Remote Working Age” in Bridgehead Communication’s ‘The Loop’

The Global Remote Work Revolution and the Future of Work

Dave Cook, who has been collaborating with us on the eWorkLife Remote Work study has published a chapter in The Business of Pandemics book: The Global Remote Work Revolution and the Future of Work.

Media interview: Londoners urged to do ‘pretend commute’ during Covid-19 lockdown to protect health

Prof Anna L Cox is quoted in the London Evening Standard. Londoners urged to do ‘pretend commute’ during Covid-19 lockdown to protect health By Nicholas Cecil

Remote-work visas will shape the future of work, travel and citizenship

During lockdown, travel was not only a distant dream, it was unlawful. Some even predicted that how we travel would change forever. Those in power that broke travel bans caused scandals. The empty skies and hopes that climate change could be tackled were a silver lining, of sorts. COVID-19 has certainly made travel morally divisive.

Amid these anxieties, many countries eased lockdown restrictions at the exact time the summer holiday season traditionally began. Many avoided flying, opting for staycations, and in mid-August 2020, global flights were down 47% on the previous year. Even so, hundreds of thousands still holidayed abroad, only then to be caught out by sudden quarantine measures.

In mid-August for example, 160,000 British holiday makers were still in France when quarantine measures were imposed. On August 22, Croatia, Austria, and Trinidad and Tobago were added to the UK’s quarantine list, then Switzerland, Jamaica and the Czech Republic the week after – causing continued confusion and panic.

This insistence on travelling abroad, with ensuing rushes to race home, has prompted much tut-tutting. Some have predicted travel and tourism may cause winter lockdowns. Flight shaming is already a cultural sport in Sweden, and vacation shaming has even become a thing in the US.

Amid these moral panics, Barbados has reframed the conversation about travel by launching a “Barbados Welcome Stamp” which allows visitors to stay and work remotely for up to 12 months.

Prime Minister Mia Mottley explained the new visa has been prompted by COVID-19 making short-term visits difficult due to time-consuming testing and the potential for quarantine. But this isn’t a problem if you can visit for a few months and work through quarantine with the beach on your doorstep. This trend is rapidly spreading to other countries. Bermuda, Estonia and Georgia have all launched remote work-friendly visas.

I think these moves by smaller nations may change how we work and holiday forever. It could also change how many think about citizenship.

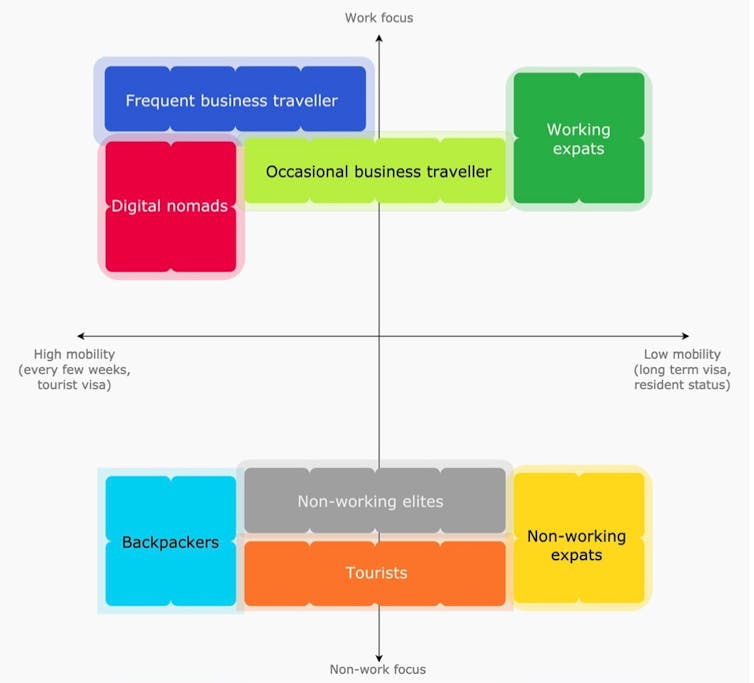

Digital nomads

This new take on visas and border controls may seem novel, but the idea of working remotely in paradise is not new. Digital nomads – often millennials engaged in mobile-friendly jobs such as e-commerce, copywriting and design – have been working in exotic destinations for the last decade. The mainstream press started covering them in the mid-2010s.

Fascinated by this, I started researching the digital nomad lifestyle five years ago – and haven’t stopped. In 2015, digital nomads were seen as a niche but rising trend. Then COVID-19 paused the dream. Digital nomad Marcus Dace was working in Bali when COVID-19 struck. His travel insurance was invalidated, and he’s now in a flat near Bristol wondering when he can travel.

Dace’s story is common. He told me: “At least 50% of the nomads I knew returned to their home countries because of CDC and Foreign Office guidance.” Now this new burst of visa and border policy announcements has pulled digital nomads back into the headlines.

So, will the lines between digital nomads and remote workers blur? COVID-19 might still be making international travel difficult. But remote work – the other foundation of digital nomadism – is now firmly in the mainstream. So much so that remote work is considered by many to be here to stay.

Before COVID-19, office workers were geographically tethered to their offices, and it was mainly business travellers and the lucky few digital nomads who were able to take their work with them and travel while working. Since the start of the pandemic, many digital nomads had to work in a single location, and office workers have become remote workers – giving them a glimpse of the digital nomad lifestyle.

© Dave Cook and Tony Simonovsky, Author provided

COVID-19 has upended other old certainties. Before the pandemic, digital nomads would tell me that they despised being thought of as tourists. This is perhaps unsurprising: tourism was viewed as an escape from work. And other established norms have toppled: homes became offices, city centres emptied, and workers looked to escape to the country.

Given this rate of change, it’s not such a leap of faith to accept tourist locations as remote work destinations.

A Japanese businessman predicted this

The idea of tourist destinations touting themselves as workplaces is not new. Japanese technologist Tsugio Makimoto predicted the digital nomad phenomenon in 1997, decades before millennials Instagrammed themselves working remotely in Bali. He prophesied that the rise of remote working would force nation states “to compete for citizens”, and that digital nomadism would prompt “declines in materialism and nationalism”.

Before COVID-19 – with populism and nationalism on the rise – Makimoto’s prophecy seemed outlandish. Yet COVID-19 has turned over-tourism into under-tourism. And with a growing list of countries launching schemes, it seems nations are starting to “compete” for remote workers as well as tourists.

The latest development is the Croatian government discussing a digital-nomad visa – further upping the stakes. The effects of these changes are hard to predict. Will local businesses benefit more from long-term visitors than from hordes of cruise ship visitors swarming in for a day? Or will an influx of remote workers create Airbnb hotspots, pricing locals out of popular destinations?

It’s down to employers

The real question is whether employers allow workers to switch country. It sounds far-fetched, but Google staff can already work remote until summer 2021. Twitter and 17 other companies have announced employees can work remotely indefinitely.

I’ve interviewed European workers in the UK during COVID-19 and some have been allowed to work remotely from home countries to be near family. At Microsoft’s The New Future of Work conference, it was clear that most major companies were mobilising task forces and would launch new flexible working policies in autumn 2020.

Countries like Barbados will surely be watching closely to see which companies could be the first to launch employment contracts allowing workers to move countries. If this happens, the unspoken social contract between employers and employees – that workers must stay in the same country – will be broken. Instead of booking a vacation, you might be soon booking a workcation.![]()

Dave Cook, PhD Researcher, Anthropology, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

I’ve lived through many disasters. Here is my advice on “productivity”.

Great twitter thread from Dr Aisha Ahmad which I’ve unrolled here

@ProfAishaAhmadInt’l Security prof @UTSC & @UofT, Chair WIIS-Canada, boxer. Author of award-winning book Jihad & Co. https://bit.ly/2uqQVWD

Academic peeps: I’ve lived through many disasters. Here is my advice on “productivity”. First, play the long game. Your peers who are trying to work as normal right now are going to burn out fast. They’re doomed. Make a plan with a longer vision. /1

Second, your top priority is to stabilize and control your immediate home environment. Ensure your pantry has sensible supplies. Clean your house. Make a coordinated family plan. Feeling secure about your own emergency preparedness will free up mental space. /2

Third, any work that can be simplified, minimized, and flushed: FLUSH IT. Don’t design a fancy new online course. It will suck & you will burn out. Choose the simplest solution for you & your students, with min admin. Focus on getting students feeling empowered & engaged. /3

Fourth, give yourself a proper mental adjustment window. The first few days in a disaster zone are always a write-off. But if you give yourself that essential window, your body and mind WILL adjust to the new normal. Without that mental shift, you’ll fall on your face. /4

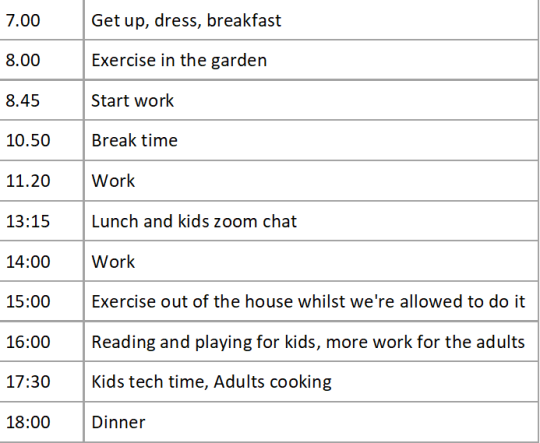

Fifth, AFTER you experience the mental shift, build a schedule. Make a routine. Put it on a weekly calendar with time blocks. Wake up early. Put the most important parts first: food, family, fitness. Priority 1 is a stable home. Then add windows for achievable work goals. /5

Sixth, cooperate with your brain. For me, I need to ease into heavy-duty academic writing. So I do admin in the morning, and then dip my toe into papers and book projects around noon. Tick off accomplishments, no matter how small. Trust and support your mental shift. /6

It’s unreasonable to demand your body & brain do the same things under higher stress conditions. Some people can write in a war zone. I cannot. I wait until I get back. But I can do other really useful things under high stress conditions. Support your continuing mental shift. /7

For my PoliSci colleagues: this phenomenon should change how we understand the world. So let this distract you from your work. Because the world is supposed to be our work. May this crisis dismantle all our faulty assumptions and force us into new terrain. /8

And finally, we can check on our neighbours, reach out to isolated people, and volunteer or donate as we can. Because at the end of the day, our papers can wait.

What crowdworkers can teach us about working at home

As schools across the UK closed their doors on Friday families focused on how they were going to create a coworking space at home. They spent their weekend moving furniture, clearing out spare rooms, refinding extension cable usually reserved for the xmas tree lights so as to create a new home office that could fit the whole family. We are fortunate enough to have a small extension that is open plan to our dining room that we can fit 3 of us into and we’ve squeezed an extra deskspace on the edge of the dining room so that we each have our own place to work.

My new coworkers include a teen, a tween who are used to spending their days at school and doing a bit of homework at the end of the day. The fourth member of our team is a middle-aged man who is used to getting most of his ‘deep-work’ done in the office, and only using home for catching up on email. None of them are happy to be here! I, on the other hand, am used to having the place to myself to get on with ‘deep work’ and use my office for face to face meetings. I’ve been working at home for at least a day a week (usually more) for the last 16 years, first motivated by avoiding the crazy costs of commuting into London and then to facilitate the juggling of school pick-ups that comes with family life.

Our new normal means scheduling our day around the timetable of a secondary school. They’re encouraging the teen to do the work set during standard lesson time and of course that’s completely necessary for live online lessons. The tween is doing a fantastic job of following the lesson plans that have been emailed over by his teacher this morning. And I’ve realised that this timetable isn’t that different that one I followed on a writing retreat last year so this might actually work well for all of us. I don’t often take a 20 minute break in the middle of my morning but it was lovely to stand out on the patio in the sunshine whilst having a cup of tea.

We all have different needs in this space. Two of us have online meetings with work colleagues and students, as well as video lectures to record. The teen is in the middle of an online lesson in google meets as I type – it seems that he doesn’t have to say anything (thank goodness) but I can still just about hear the teacher’s voice from his headphones. Being physically all in the same space isn’t going to work for all hours of the day so meetings and lecture recordings are going to have to be made from bedrooms. Connecting socially online is also important now we are distancing ourselves physically from everyone else and the kids need time to talk to their friends so we’ve set up daily meetings for them with online conferencing software so that they can hang out together.

We’re also trying to follow the WHO guidelines that state that children and youth aged 5–17 should accumulate at least 60 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity daily https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_young_people/en/ Walks and runs around our local streets and park involve taking swerving routes away from people who don’t seem to have worked out that moving into single file when you are coming face to face with someone is probably a good idea! Yesterday a group stopped still as they saw us coming towards them – all 4 of them stood side by side across the path!

In this new coworking world, the research I’ve been doing with my PhD student Laura Lascau into the environments in which remote crowdworkers do their work has taken on new personal significance. There are many parallels between the challenges experienced by crowdworkers and those that many families will find themselves facing this week and I’ve tried to take on board what we have learnt when designing our new coworking arrangements. In the rest of this post I’ll summarise some of the findings from a paper we published last year and what we can learn from them:

Laura Lascau, Sandy J. J. Gould, Anna L. Cox, Elizaveta Karmannaya, and Duncan P. Brumby. 2019. Monotasking or Multitasking: Designing for Crowdworkers’ Preferences. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Paper 419, 1–14. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300649 (The full paper is available open access here https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10066164/1/1.%20monotasking-multitasking-CHI2019.pdf )

We surveyed people who work from home regularly about what works for them and have been able to extract some helpful tips for others that find themselves in this situation now.

Making an office space

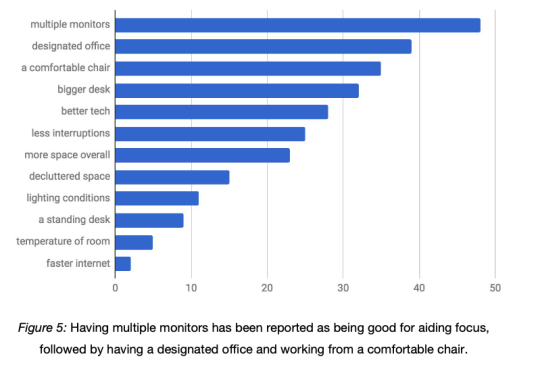

What changes would crowdworkers make to their spaces? Here are the top 4 things that they felt would improve their home work space.

- multiple monitors – our participants were clear that having multiple monitors would help them to get their work done more easily rather than working only from a small screen.

- have designated office spaces – they were also big fans of having a designated office space to work in. We pick up on this below when considering working around other people

- more comfortable chairs – having to made do with a corner of the sofa, or someone’s bed as a workspace was common. Having a comfortable chair was see

- larger desks – having a space to lay out everything they needed to complete their work was important

Working around other people

What are the most common challenges to focusing on work at home?

- presence of other people

- having the TV on

- pets

- digital distractions

About 40% of our participants worked from a shared space and struggled with integrating their demands of the different types of work they do with the constraints of their physical environment. As one of our participants told us:

“I would first and foremost move it into a private room. I miss out on numerous [jobs] because I am unable to record audio or video due to the fact others are making noise around me or would be in the webcam video. It also provides many distractions since it’s in the front room. A personal private room would be the best upgrade.”

Tip: Find out from everyone what kinds of activities they need to do in their day in order to identify what kind of spaces you need. Are you able to provide everyone with their own working space? If not, do you need a quiet working space for those doing ‘deep work’ and another place where people can have online meetings? Is this going to work every day or do you need to agree to rotate around? Check in frequently with each other to make sure everyone is getting the type of space they need.

Managing distractions

What helps workers focus on their work?

- quiet spaces,

- limited distractions,

- background entertainment (mainly listening to music)

Our participants told us about the strategies they use to manage distractions that come from other people:

“I use noise cancelling headphones. I tune out environmental noises or activities. I remain focused on what I’m doing. I do not engage in more than one activity at a time unless the [the work] require me to do so. I do not eat or listen to music while I work. I tend to work when the environment is calm rather than when I know those around me will be active.”

“I try to work during times I know the kids are being independent or napping.”

Tips: Sharing your work space with people who are prone to interrupt you is always difficult. Agreeing on a daily schedule that everyone agrees to might be helpful for helping to plan when you’re going get your work done. Remember that everyone feels that their own work is important so you can’t have one person dominating the way the space is being used. There’s going to have to be a lot of compromise.

If you have young children then talk to them about what they can be doing whilst you get on with your work. Some children can get lost in a book or happily play for hours with their toys. Most children can be occupied by tv or digital games. If you can, stick on some headphones and power through! Perhaps young children could be entertained by grandparents through videoconferencing software – they could read stories to them, or have a chat.

Work-life boundary management and leisure time

People vary in terms of how they tend to manage their work-life boundaries. Some people prioritise work, others non-work, and some try to do both. People also vary in terms of how separate they like to keep these parts of their lives: ‘integrators’ are happy switching frequently between one and the other, perhaps to the point where these doesn’t seem to be a boundary at all. ‘Separators’ like to keep them completely separate and wouldn’t ever contemplate working at home or at the weekend.

It won’t come as a great surprise to know that we saw that people who work from shared spaces such as family homes experience a far greater number of interruptions from personal matters when they were trying to work than those who were working from private spaces.

Tips: If you or your partner are separators then recognise that you’re likely to find this new co-working environment challenging and that it will take time to adapt to it. Again a schedule can be helpful here so that you block time for work and time for non-work. Remember to schedule non-work activities whether that’s time with friends, taking part in an online “pub” quiz or one of the many online exercise classes that have suddenly appeared.

Remote working: the new normal for many, but it comes with hidden risks – new research

Matej Kastelic

Many of us have had little choice but to resort to remote working in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. It is just days since Google, Apple and Twitter were making headlines by ordering their employees to work from home, but you could now say the same about lots of companies.

Whatever you think about this style of working, the trend is increasing. Remote working was already growing fast – more than doubling since 2005 to 4.7 million workers in the US, for example. If you believe recent headlines, the transition is all too easy and seamless.

Yet the march towards this utopian future has been uneven – witness IBM’s decision to dump remote working several years ago, because it was preventing innovation and collaboration. I have just published research that highlights additional challenges and difficulties. And if people don’t approach remote working in the right way, they risk making their work lives worse.

Pros and cons

When discussing remote working, academics and the media have been split into opposing camps. The pro camp talk about cuttng out commutes, increasing quality family time and productivity and achieving a better work-life balance. Sceptics reply that flexibility comes at a cost. They warn about losing social interaction, nuance and community – and potentially becoming less productive. These give us mixed messages when we need certainty.

As an anthropologist, I’ve spent the past four years researching how people adjusted to becoming an extreme type of remote worker known as digital nomads. These workers move from country to country, always working online. I followed more than 50 in total, employed in a range of jobs including computer coding, graphic design, online marketing and travel journalism.

After an initial honeymoon period, remote working quickly became too isolating for over 25% of my participants. As one said, “Some aren’t naturally self-motivated, and no end of self-help books will change that”.

One solution turned out to be the coworking space. It gave a sense of community and face-to-face interaction, but more important was just to be around other workers – academic jargon for this is co-presence. As a remote employee working in ecommerce explained: “Just being around other folk working turbocharges your day.”

I completely understand this sentiment. I wrote most of this article in a coworking space, and just being around others tapping away at their keyboards creates a feeling of effortless productivity.

Yet things change quickly. Coworking spaces are not going to be an option for many people for a while. Some of those in house shares will be able to recreate the same environment at home. There are various forms of coworking space etiquette that can be adopted at home, such as having quiet zones for focused work and having separate areas for voice and video calls.

Digital discipline

If working near other people is important, the need for a disciplined work life is everything. For my research participants, this was the secret ingredient in sustaining remote working – whether the discipline was self-imposed or externally set by deadlines.

My participants never discussed discipline at first. The initial excitement of remote working made them productive for a while. But after a few months, motivation became harder. At this point, some participants gave up on this lifestyle.

Moshbidon

Those who thrived tended to be more strict, ensuring they went to coworking spaces every day and put phones and social media noise out of reach. Many also set up rituals. One graphic designer deliberately chose to work in a space that was 15 minutes walk from their home, to “mentally gear up for work” on his way in and to decompress before he got home.

Fascinatingly, here was a worker who had not only given up one office for another, but was recreating the daily commute. And just because coworking spaces are off limits at the moment it doesn’t mean you can’t consider equivalent rituals. It is still an option to build a short walk into the beginning and end of the working day, thereby creating a clear division between your home and work life.

Always on, always available

Digital technology may free people to work remotely in the first place, but it also causes unforeseen problems. My participants reported a growing expectation to be available 24/7, reflecting similar findings in other studies.

This is an issue for the entire workforce, but it is arguably exacerbated by remote working. Our 24/7 work culture didn’t happen overnight, or because of coercive managers. Instead, the perceived division between work and non-work has steadily disappeared over time, while few of us were paying attention.

Sociologist Judy Wajcman argues that this mentality is even restructuring how we think about time, as Silicon Valley designs devices and apps that urge us all on a never-ending quest for productivity and self-discipline. Besides work, the ways in which we read books, watch TV, exercise and meditate can now be timeboxed into app-sized chunks as well.

This culture has led some remote workers to experience mental health issues and burnout. Reflecting back on his burnout, one interviewee called Sam explained:

I didn’t have the concept of free time until I found myself scheduling four-hour meetings in my diary titled ‘downtime’. It’s insane; I look back at this period in my life and wonder why it took so long to burnout.

Aldeca Productions

We all need to keep an eye on this dangerous trend. It is crucial to set clear boundaries between home life and work and not put pressure on ourselves to be available outside working hours – particularly during a crisis when many of us will need to support family and friends.

Finally, remote working could well become permanent for many people. Many companies were encouraging staff to work elsewhere to reduce office costs before the outbreak, and this will probably be all the more attractive to the businesses that survive this crisis. One wonders if in ten years we will look back from our remote workstations and remember 2020 as the year we last went into the office. Either way, we need to be careful. Remote working always tantalises with the promise of freedom, but it can end up delivering the exact opposite.![]()

Dave Cook, PhD Researcher, Anthropology, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.