Home » Posts tagged 'Videogames'

Tag Archives: Videogames

Measuring Immersion: The IEQ Explained

Are you interested in studying the psychology of gaming or immersive experiences? The Immersive Experience Questionnaire (IEQ) is an essential tool that can help you measure immersion—the psychological experience of being deeply engaged in a task, such as playing a video game. Whether you’re investigating what makes games so captivating or analyzing the factors that influence immersion, the IEQ provides a structured, validated approach to quantify this fascinating phenomenon.

What Is the IEQ?

The Immersive Experience Questionnaire (IEQ) is a tool designed to measure the degree of immersion an individual experiences during a particular activity, such as playing a game or using a virtual reality system. Immersion is assessed across five dimensions:

- Cognitive Involvement: The mental effort and focus dedicated to the activity.

- Real-World Dissociation: The extent to which an individual loses awareness of their surroundings.

- Challenge: How well the difficulty of the task matches the individual’s skills.

- Emotional Involvement: The level of emotional engagement with the activity.

- Control: How much autonomy and ease the individual feels during the activity.

The IEQ uses a combination of Likert-scale questions to measure these dimensions, offering a detailed picture of how immersive an experience was.

Resources to Get Started

To help you score and interpret the IEQ, we’ve prepared two resources:

- IEQ Scoring Guide: A document that explains how to calculate scores for each dimension of the IEQ.

- IEQ Scoring Spreadsheet: A pre-formatted spreadsheet where you can input participants’ responses and automatically calculate their scores.

These resources will save you time and ensure that your analysis is accurate and consistent.

How to Use the IEQ

- Administer the Questionnaire: Give the IEQ to participants after they have completed the immersive activity you’re studying. Ensure they understand the questions and the context in which they should respond.

- Collect Data: Make your own copy of the spreadsheet. Gather responses and enter them into the IEQ Scoring Spreadsheet.

- Score the Responses: Use the guide and spreadsheet to calculate scores for each dimension as well as an overall immersion score.

- Interpret the Results: Compare scores across participants or experimental conditions to uncover patterns or insights about immersion.

Jennett, C., Cox, A. L., Cairns, P., Dhoparee, S., Epps, A., Tijs, T., & Walton, A. (2008). Measuring and defining the experience of immersion in games. International journal of human-computer studies, 66(9), 641-661.

’Jumping Out from the Pressure of Work and into the Game: Curating Immersive Digital Game Experiences for Post-Work Recovery

Mella, J., Iacovides, I., & Cox, A. (2024). ’Jumping Out from the Pressure of Work and into the Game: Curating Immersive Digital Game Experiences for Post-Work Recovery. ACM Games: Research and Practice.

In this paper we explore how digital games can be used for psychological recovery after work. We conducted a study involving eleven participants who played games post-work and participated in follow-up interviews.

Key points:

- Immersion in Gaming for Recovery: The study focuses on how immersion in gaming can aid in the recovery from work-related stress. Immersion is seen as a multifaceted experience that can help players detach psychologically from work stresses and recover their mental resources.

- Strategies for Immersive Experience: Participants reported various strategies to enhance their gaming immersion to optimize recovery. These strategies included selecting games based on their ability to provide challenge, mastery, relaxation, or a sense of control.

- Framework of Immersion Optimization: The research contributes a framework for understanding how different elements of games can be used strategically to facilitate recovery. This includes aspects such as game choice, gameplay settings, and in-game goals.

- Impact of Gaming on Recovery Experiences: The study found that strategic gaming can effectively provide recovery experiences such as psychological detachment, relaxation, and mastery. These experiences are crucial for recuperating after work and preventing long-term stress effects.

- Methodological Insights: The use of a laddering methodology provided detailed insights into the specific components of gaming that support recovery. This approach highlighted the direct connections between game features, player experiences, and recovery outcomes.

- Implications for Game Design and Use: The findings suggest that both game developers and players can benefit from understanding how different game features can be used to enhance post-work recovery. The study advocates for games designed with features that support recovery needs.

COVID Ward

A blogpost by Emma Holliday, student on MSc HCI 2019-2021

Getting into the video games industry was originally my inspiration for studying Computer Science. As I learned about the often toxic work environments (and sexism) in the gaming industry, I decided to leave this dream behind and went into software development instead. That’s why I’m so amazed and thrilled to have actually designed and built my own game and, even better, to have won an award for it.

Click here to play the game! Spoilers below!

The game itself was built as part of my coursework for the Serious and Persuasive Games module (led by Prof Anna Cox) on the Human-Computer Interaction course at UCL. (Even though I had somewhat given up on a career in the gaming industry, I still really loved games and would take any excuse to learn about them and play them.) Something that really stood out to me during the lectures was the concept of the “Magic Circle”, an idea that games exist within set boundaries that are separate to the real world. This means that different rules apply within game (e.g. violence is allowed), actions in the game don’t have consequences in the real world, and actions in the real world don’t apply to the game. I immediately challenged this – I’m sure we’ve all had that gaming session that left friendships a little sour even after the game had finished, learnt something new or even strengthened our relationships. I personally believe, particularly with narrative-based games, it is very unlikely to not leave some lasting impression in the real world long after the game has been played. As such, I designed a game that would exploit breaking the “Magic Circle” by including people’s real-world actions into gameplay. My hopes were that, by breaking the “Magic Circle” upfront, this would weaken the boundaries between the game and the real world, encouraging players to take experiences from the game back into real life.

My time studying this module was during the COVID-19 pandemic which also provided a lot of inspiration, largely because it was inescapable and incredibly topical. Other games which we studied during the module were also influential, particularly those on blame culture in nursing (such as Nurse’s Dilemma and Patient Panic). All of this culminated in my game, COVID Ward, where players take on the role of a nurse working in the intensive care unit during the COVID-19 pandemic. The gameplay is quite simple, players use arrow keys to control the nurse and spacebar to administer aid to patients in the ward. Patient health deteriorates over time and they will eventually die if their health becomes too low while fully healed patients are able to leave the ward. The game plays out as levels representing 12 hour shifts, so time is limited and the nurse character can only do so much in a day. In between levels is where the “Magic Circle” is broken; the player is asked a question relating to their real-world actions during the pandemic and their answer affects the number of patients admitted to the ward during the next level. For example, the question may ask if the player always wore a mask while on public transport. If the player answers “no”, there would be more patients in the ward the next day than if they had answered “yes”. Through this, players see the their actions directly associated with the effects on other people and healthcare staff.

The game was refined iteratively thanks to playtesting with my friends, fellow students, and staff on the Serious and Persuasive Games course. Finally, a user study was completed to test if the game had the desired effects of making people feel more responsible for their actions, encouraging them to follow COVID-19 safety guidance more closely and increasing empathy for nursing staff. Though it was a small scale study, initial results were very positive and suggested that the game had achieved its goal in terms of attitude change. Qualitative responses from participants repeatedly mentioned the use of their real world actions and suggested it was both engaging and encouraged them to reflect more deeply on their actions. As such, breaking the “Magic Circle” is a promising technique for persuasive games which warrants further research.

In terms of development, the game was built using Game Salad (a no-code game authoring tool). Though I’m familiar with code, (and there were times I wished I was using code!) GameSalad did provide a really quick way to get started and put ideas together without too much learning overhead. Having since tried to pick up Unity, I can say Game Salad is definitely a lot quicker to get your ideas into something working, which is crucial for iterative development. Game Salad also made it very easy to publish my game so that others could play it online, which helped enormously when getting feedback and conducting the user study as there was no installation or downloads required.

In an early version of the game, everything was represented by incredibly simple shapes and numbers. While I support the concept of primarily using the mechanic to deliver the message, as demonstrated remarkably in Brenda Romero’s games, I felt my game would benefit from graphics and sound effects to help immerse the player and reinforce the narrative that these were real people affected by their actions, encouraging stronger empathy. Given the short time frame (and that I am only one person who is not talented enough to do everything from scratch!) I was exceedingly grateful for assets created by other artists which allowed me to create something that was much more complete than I could have achieved on my own. I found the music by Bio_Unit on Free Music Archive and got sound effects from Kenney.nl (a fantastic source for several free assets!) I paid for some pixel-art assets from Malibu Darby through Humble Bundle which, very fortunately, had a game dev bundle just as I was building the game. I also dabbled in editing the pixel art myself to customise it to my game. If you’d like to give that a go, I recommend aseprite.

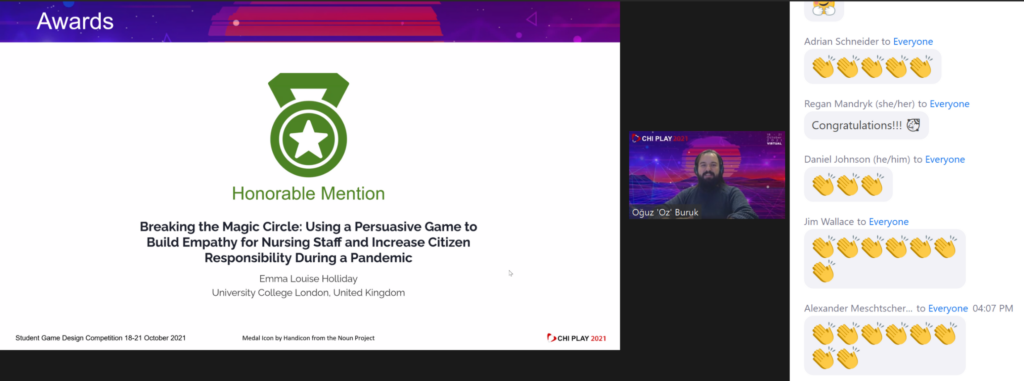

Overall, I was really happy with my game and the results of the user study. Prof. Anna Cox had suggested that the class submit their work to the CHI PLAY student game competition. Earlier in my time at UCL, Prof. Catherine Holloway had encouraged us to always try and share our work with the academic community and introduced me to Student Research Competitions. These are often held across different ACM conferences (such as SIGCHI, SIGACCESS, CHIPLAY) and felt much more approachable to me as the level of work expected was closer to what I had already done for my coursework. As such, I decided to go for it and submit my game and a paper detailing the user study to CHI PLAY 2021’s Student Game Design Competition. I didn’t really expect to win anything, but I was just happy to share my game in the hopes it might have a life beyond my university coursework grades.

So I was very excited when I heard back to find out my game had been accepted! It turns out, 8 of the 19 submissions were accepted to the conference as finalists. This did mean, however, that I had a bit more work to do! I updated my paper to respond to the reviewers’ comments, battled with the proper formatting and TAPS submission system (though the support staff are really helpful), and created a reaction video to be played at the conference. I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t stressful (largely because it fell right across the deadline for my final MSc dissertation!!) but it was definitely worth it to see my work presented at the conference and all the interest it generated. Even more so when I was announced as receiving an honourable mention for the competition! I also got to attend the entire conference – though you don’t have to be an author to do so – and joined lots of interesting talks and presentations across all aspects of games.

It was really rewarding finding myself back in the games industry, in a sense, but from a completely different direction than I had ever imagined and one that was much better suited to me and my passions. It was even more rewarding to know that I had contributed to it and that, maybe one day, my research will have an impact on the games I end up playing on my sofa.

Find out more about the competition and see the other entries

Rewards Placement can Determine Engagement in Apps

Our new research paper coauthored with Dr Diego Garaialde and Dr Ben Cowan from UCD, identifies the best location to place rewards when using gamification to motivate users. The research paper, which was published in the International Journal of Human-Computer Studies and is available online on Science Direct (sciencedirect.com), highlighted that placing rewards early on in the user interaction was more effective and encouraged users to use the app more.

Gamification has become a common technique for incentivising users to engage with an application however the placement of this tactic and how it impacts on a user is often not considered during the design process. We found that the value a user places on a reward diminishes the further into the future it is and placing rewards early in the interaction sequence leads to an improvement in the perceived value of that reward.

Speaking about the findings Diego Garaialde said: “Rather than rewarding after longer interactions with the app, which is common in current gamified applications, designers should consider rewarding users early for deciding to interact with the app in the first place.”

The full paper can be found online.

(An earlier version of this post originally appeared on the blog of the ADAPT centre)

Talk: Games for Academic Life

Prof Anna L Cox gives keynote speech “Games for

Academic Life” at GALA 2020, Games and Learning Alliance conference.

A copy of the slides is available for download.

You are suddenly part of a virtual team.

Reblogged from an article by Evelyn Tan describing our work on using games to support the creation of digital teams

We were pushed into the age of fully remote work as abruptly as COVID-19 exploded across the globe. We are all suddenly part of a virtual team. We had no idea this was coming. And to be honest, it doesn’t seem like remote work is going to go away after things go back to “normal”.

Organisations are still scrambling to figure out how to deal with the ramifications of virtual work.

On the other hand, managers and team leaders are trying to figure out how to best keep their teams afloat.

But here’s some good news: Research on virtual teams — the challenges they face and how to make them effective — has been around since the Internet became a thing.

In this article, I highlight some of the most pressing challenges that you are going to face (or admittedly, have already faced) now that you are part of a virtual team. These challenges are primarily related to team processes — how do we get things done. I will also highlight some actionable solutions, based on scientific literature.

This article is meant for teams who are clear on their purpose, goals and roles but are struggling to set the right processes in place to achieve them. Without the former, the latter won’t get you anywhere.

Fun fact. Virtual work or remote work is also known as ‘telecommuting’, to refer to work where commuting time is reduced.

Problem 1: You can’t monitor your team. Trust is essential.

An effective virtual team requires a lot of trust because there is an increased sense of uncertainty. Since you cannot see people physically, you cannot monitor them like you previously could when co-located. If you micromanage, you will be exhausted, your colleague will be annoyed, and everyone becomes less productive. You need to trust that everyone has the team’s best interest in mind.

I like this definition of trust by Wilson, Straus and McEvily (2006, p.3)

Trust is the confident positive expectations about the conduct of another

The whole team becomes more productive when there is trust because less time will be spent checking up on each other and making contingency plans. We can have confidence that our team members will deliver on time.

Assuming that everyone is clear on their roles and their goals, how can we be confident that people are actively working towards them?

Solution: Encourage predictable communication through substaintial and timely responses.

In situations with high uncertainty, one way to build trust is to provide a lot of reasons to warrant trustworthiness. For virtual teams, this means exhibiting communication behaviours that give people a reason to trust you.

In an early study on the initial and final trust levels of global virtual teams, teams that were characterised as “high initial and high final trust” exhibited enthusiasm and excitement in the beginning and sustained frequent communication. Communication was not strictly task-focused but also included social content (i.e. things about their life outside of work).

This shows that teams with high levels of trust get there because they spend time developing all aspects of trust — trust based on rational reasons (e.g. Peter has always delivered his work on time) and trust based on emotional ties (e.g. Peter genuinely cares about my well-being).

Having substantial communication and timely responses helps to build up a history of reciprocal, positive interactions. The more actions someone has performed, the easier it is to predict or approximate their future behaviours. This feeds into our perception of their trustworthiness, which gives us confidence in our team members even if we do not see them. But this doesn’t mean we should be flooding the chat. Rather, our responsiveness should signal that we remain committed to achieving our goal.

The key point to remember is that trustworthiness is a function of prior successful ‘trust transactions’. Therefore, for new virtual teams, having substantial communication provides opportunities to validate trust, and timely responses strengthen perceptions of trustworthiness. As the team develops, less frequent communication is needed to maintain trustworthiness.

Problem 2: The way we interact with our team is going to change. Set guidelines for behaviour.

Spatial separation affects how team members interact with one another. Since the ability to walk up to a colleague and have a face-to-face conversation is suspended, interactions will become more effortful and less fluid. As shown in this study, this means that we can expect lags in information exchange, a higher chance of misunderstandings, and fewer attempts to seek information.

Since communication is asynchronous, it can also become overwhelming — if you’ve ever missed a text conversation that you are not an active participant of only to come back to 100 unread messages, you’ll know how this feels. A flurry of text chat, and endless back-scrolling could have been avoided through a simple phone call.

Solution: Use the right communication channel. Establish norms of functioning

Choose an appropriate communication channel. Effective virtual teams match the communication channel to the function of the interaction, or the task at hand. More complex tasks would require channels that allow higher synchronicity. For example, if the point of the interaction is to have a discussion that involves resolving previous ambiguities, brainstorming and problem solving, with a decision at the end, a video call is most appropriate as lags in information exchange are likely to be counterproductive. Having this interaction over text chat would be overwhelming. On the other hand, if the point of the interaction is to gather information, using email, text chat and phone calls will suffice.

Establish norms of functioning. Norms are particularly important in situations with high uncertainty (i.e. virtual teams) because it provides guidelines on how to behave. For virtual teams, establishing a guideline for how the team should function helps to regulate communication and work.

Day-to-day functions.

It is important to establish norms related to monitoring progress because there will be high ambiguity on what is appropriate behaviour. For example, everyone should be clear on how often to check and respond to messages. Everyone should also be clear on how often to provide status updates and check on other member’s status. By explicitly setting these norms, these behaviours are seen as necessary for team success, not because of paranoia or a lack of trust. On the plus side, research shows that trust is built when people adhere to norms.

Team meetings.

Ensure everyone has a chance to speak and contribute. High-performing teams are marked by equally distributed communication, virtual or not. When it is their turn, do not cut anyone off. Give people ample time to speak. As found in a study on predicting cohesion in virtual team meetings, the pause time between a person’s turn and the same person’s next turn was predictive of highly cohesive teams. This means that everyone should have a turn to speak and be given time to talk. If anyone is dominating the conversation, reel them back and encourage others to chip in.

It is also important to encourage people to be actively involved in the meeting, even if they are not speaking. The same study found that cohesion can be predicted most accurately by the amount of visual activity a person exhibits when they are not speaking. Gestures like nodding, for example, signal active listening. In video calls, where virtual team meetings likely take place, everyone can be seen head-on. This means that it is easy to tell who is listening and who isn’t. Norms should be established around engagement and participation in virtual team meetings.

Problem 3: Everybody is going to feel more distant. Invest time in team bonding.

When we are co-located, interpersonal relationships develop through spontaneous interactions with our colleagues. There are intentional interactions as well, but the ‘random chats’ and ‘coffee breaks’ are actually crucial to developing bonds. It has been found to increase cohesion and productivity.

When teams become virtual, there is no more water cooler to congregate around. Since communication is more effortful, it can be heavily task-focused and less about the social lives of others. If your team members do not already have strong interpersonal relationships, virtual work can make them feel more distant from their colleagues.

Solution: Make time for social chat and play video games together.

In the current climate, it can be easy to just make virtual everything that we used to do in a co-located space. Virtual Friday night drinks and virtual pub quizzes are the go-to post-work activities. These activities usually take place over a video call, but as the world has come to realise, conducting typically co-located experiences through a screen is exhausting. Using the same virtual space for work and fun doesn’t provide enough separation. If people are on the same platform that they use to do work (e.g. Zoom, Teams, Skype), with work-related people (i.e. colleagues) but doing an activity that is not work-related, it might not create enough mental distance for recuperation — social activities will still feel like work.

So, consider playing a video game instead.

By this, I mean games where everyone is represented as an avatar in a virtual world, and video call is not required. ‘Zoom Fatigue’ has become a thing and is so taxing on our brain because video calls require greater attentional effort and make us feel more self-conscious. Playing video games together, on the other hand, is a shared activity that lets people truly wind down. And there are several reasons why.

Video games are unique because they are immersive experiences — they draw people into the game and make them momentarily forget what’s happening in the real world. So it’s no surprise that digital games have been found to aid post-work recovery. And one of the reasons is because it helps people to detach both physically and mentally from work.

Video games are also completely different virtual environments. Everyone is likely represented as an avatar that does not resemble their ‘real world’ selves. People can embark on activities that they do not usually do in their day-to-day.

Video calls are also not required — using ‘voice chat’ over Discord is the preferred method for gamers. This means that nobody will feel conscious about how they look, or about people looking at them.

Finally, you will be engaging in an activity that is inherently built for fun and enjoyment. The whole interaction has nothing to do with work and everything to do with the social experience.

So it’s no surprise that video games have been found to support deep social relationships. The game provides opportunities for shared experiences which becomes a catalyst for conversation. Bonds are formed over the experience and we learn more about the people we work with, beyond the work that they do.

Don’t know what to play? Here are a couple of 4-player team-based games that I’ve really enjoyed playing with my friends. They are easy to learn, easy to set up and don’t have high system requirements.

- Lovers in a Dangerous Spacetime (local co-op only)

- Unrailed! (online co-op)

Tying it all together.

To develop an effective virtual team, conscious and intentional effort is required. The three main challenges that virtual teams face are:

- difficulty in monitoring performance

- learning how to interact through computer-mediated mediums

- overcoming feelings of distance

In this article, I’ve highlighted how these challenges can be addressed. By focusing on developing trust, developing norms of functioning and developing social bonds, the foundation for virtual team effectiveness can be built.

The gamer in your life isn’t ignoring you, they’re blind to your presence

By Charlene Jennett, University College London and Anna L Cox, University College London

It’s irritating when you try to talk to someone playing a videogame. You tell them dinner is ready and they completely ignore you. Their eyes are glued to the screen, their fingers frantically pushing buttons. We find it rude and it has led to many an argument in the family home.

But research suggests that your children, partner or parent may not be simply ignoring you when they’re plugged in to World of Warcraft – they may be experiencing something called “inattentional blindness.”. This is when a person chooses to focus on one thing and as a result they are blind to everything else around them.

Psychologists say that our lives would be pretty chaotic if we didn’t selectively attend to things in our environment in this way. Every noise, every sight, every smell, would distract us from our goals. We would simply feel overwhelmed with incoming information and we wouldn’t be able to get anything done.

This is, in fact, a common experience of people who are diagnosed with attention deficit disorder. They feel overwhelmed because they are unable to focus their attention. People selectively attend to some things over others all the time to avoid this feeling. It’s a natural process.

But there are some activities that absorb your attention more than others. When sports players or musicians feel extremely focused on what they are doing, they might say they are “in the zone” or “in full flow”. Videogame players describe themselves as feeling “immersed” when they’re focusing. They are fully engaged in a new reality, as though submerged in water.

In our research at the UCL Interaction Centre, we have been investigating immersion for several years now, following on from studies on inattentional blindness carried out by psychologists in the 1950s and 1960s. We ask our participants to focus on one source of information while ignoring others. But where older studies had participants staring at screens or listening to sounds, we asked ours to play a video game.

In one study we asked participants to play a driving game until they were told to stop but we didn’t tell them how they would be told. Part way through the game, a small pop-up box appeared on the bottom right of the screen saying “End of experiment – click here.” Participants who performed well in the game were slower to click on the pop-up box. These were the players who rated themselves as highly immersed in our immersive experience questionnaire.

In another study we asked participants to play a spaceship game. They were told that several distracting sounds would be broadcast into the room but that they should ignore them and continue playing. Some of the sounds related to the game, such as a voice saying “space games are boring” while others were person-relevant, such as a voice saying “London is boring”. Others, such as a voice saying “collecting stamps is boring”, were simply irrelevant. At the end of the study, participants were asked to remember as many of the distracting sounds as possible. We found that participants who performed well in the game recalled fewer auditory distracters, particularly the irrelevant ones.

Our findings share quite a few similarities with traditional psychology experiments. People are less aware of visual distractions when they are highly focused on a videogame. They are less aware of auditory distractions too, with only the most relevant breaking through to their conscious attention.

Feedback and immersion

There is another a key difference between our work and those of traditional psychology experiments because unlike watching a screen, you get feedback when you play a videogame. We found that a person’s immersive experience and the extent to which they were less aware of their distracters is related to the feedback they received. Positive feedback and positive perceptions of performance are essential for keeping a person’s attention during gaming.

But even when an indicator of performance is clearly unrelated to their true performance, players are unable to prevent themselves from interpreting it as meaningful. In another version of our spaceship experiment, we rigged the game so that no matter how well the player controlled the spaceship, they would either score really well or score really badly. Despite it being obviously rigged we found the same results. Participants who scored high in the game rated themselves as more immersed and recalled fewer auditory distractions. What seems to be important for immersion then is not that players actually perform well, but that they are able to perceive themselves as performing well.

These results reveal the powerful impact that feedback has on people’s immersive experiences and their motivation to continue with an activity. Receiving regular feedback that you are doing well is pleasurable. It might even be viewed as addictive in some ways, as it motivates the player to keep coming back for more.

This in part helps us explain why the gamer in your life ignores you when you tell them it’s dinnertime. Game designers have clocked that providing feedback as part of the game encourages us to keep on playing. This same feedback encourages inattentional blindness in the player. And given that children are more prone to inattentional blindness than adults it’s a wonder that they hear anything you say.

Charlene Jennett was supported by an EPSRC DTA studentship.

Anna L Cox receives funding from the EPSRC and NIHR.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Rough day at work? Call of Duty can help you recover

By Emily Collins, University College London and Anna L Cox, University College London

Videogames have a had a particularly bad rap lately, not least after a UK coroner suggested a link between Call of Duty and teenage suicide. But recent evidence suggests that gaming can be good for us and, in particular, can help us unwind after a stressful day at work.

Many of us spend much of our working days immersed in technology. A smartphone or tablet comes with many advantages, such as flexible working, but the spread of work-based technology can add to stress too. Many people complain about the constant pressure to reply to e-mails as soon as they are received, even if that’s at 10 o’clock at night.

And even if we do switch off from work, technology is often at the centre of our home life. Watching a favourite show, keeping up to date with social media or reading online blogs are a vital component of many people’s evening activities. And while videogames were once seen as the preserve of teenagers, they have grown exponentially in popularity in recent years, largely because players no longer need a specialist console to enjoy them.

Roughly 1 out of every 4 UK adults, across ages and genders, now plays some kind of digital game at least once a week. Despite this rising popularity, digital games rarely make headlines for anything positive. Before the most recent controversy about suicide, they have been blamed for a variety of negative effects, including causing Attention Deficit Disorder encouraging acts of violence and antisocial behaviour. At the very least, they are perceived to be a bit of a waste of time, with no real, external value.

But our recent evidence suggests that not only can digital games be good for you, they may also be beneficial for your work life. Post-work recovery is a vital part of feeling prepared for the next day because it’s when you replenish the mental resources you used up during the daily grind. And it’s beginning to look like the type of activity you do during this period is important too.

Activities such as playing team sports and socialising have been found to benefit recovery but for many, this requires dedication, time and resources that simply aren’t available. So turning to activities that can be performed for brief periods of time in any location could be an ideal solution. This is exactly where digital games fit in.

Unwinding online

Our work has built on previous studies that found that those who play digital games are better recovered than those who don’t. We were interested in whether the type of game is important; the experience of playing casual games such as 2048 is likely to be very different to that of playing Call of Duty, for example. We asked participants to estimate how much time they spent playing a variety of genres of digital games in a week and then got them to complete a questionnaire to assess how much interference they experienced from work while at home and how well they recovered after gaming. They were also asked about the social support they receive from others, both on and offline.

Those who played digital games were more recovered and experienced less work-home interference than those who didn’t. And the more time people spent playing, the more recovered they felt. First-person shooter games were particularly beneficial.

While no one genre helped with every aspect of recovery, many were good for one or another. Massive multiplayer online games, which generally involve completing challenges of increasing difficulty, were good for giving players a sense of mastery. Action games, on the other hand, were related to relaxation.

We also found that out of those who claimed to have formed relationships as a result of the digital games they played, the extent of recovery was influenced by the amount of social support they had online. This suggests that digital games are effective in helping with recovery from work at least in part because they provide an opportunity to socialise.

This particular study can’t establish conclusively that the games the participants played were directly responsible for the improved recovery. It may just be that those who play digital games may simply have more time available to recover. But the findings do go some way to suggest that this causal link is possible. We are currently in the process of running more controlled studies, testing whether digital games directly improve recovery, and if so, whether the kind of game or level of immersion are important factors.

Emily Collins receives funding from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council.

Anna L Cox receives funding from the EPSRC and NIHR.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.